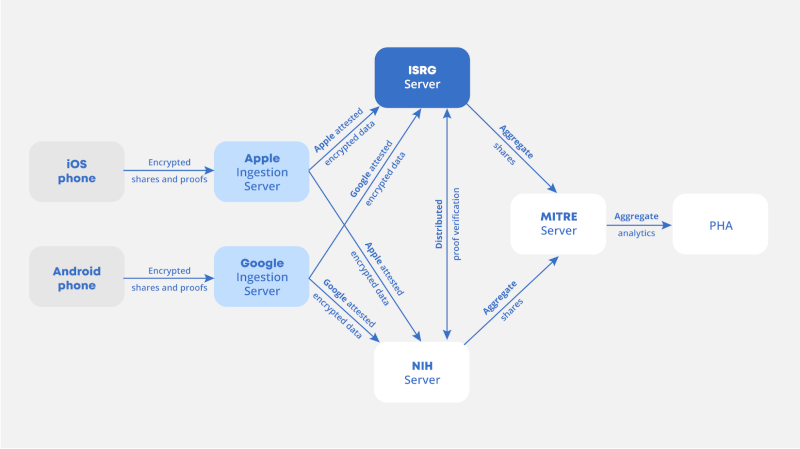

In 2020, ISRG partnered with Apple, Google, the MITRE Corporation and the National Cancer Institute (NCI) at the United States' National Institutes of Health (NIH) to build Exposure Notifications Private Analytics (ENPA). ENPA provides epidemiological metrics on the effectiveness of Apple and Google's Exposure Notifications (EN) system to public health authorities so they can tune their EN deployment's parameters and learn more about how COVID 19 is affecting the populations they serve.

Unlike traditional metrics systems, ENPA uses a novel privacy preserving aggregation technique called Prio, invented at Stanford by Dan Boneh and Henry Corrigan-Gibbs in 2017. In Prio, clients send secret shares of their inputs to two aggregator servers, each run by a different, non-colluding organization. These servers then compute aggregates over the input shares without ever learning what the inputs are. This is an instance of what cryptographers call secure multi-party computation (MPC), and we believe that ENPA is one of the largest deployments of secure MPC to date.

ISRG engineers are now working on using what we learned from shipping ENPA to build a general purpose, privacy-preserving metrics system. Along with our friends at Mozilla and Cloudflare Research, we are drafting new standards in the Internet Engineering Task Force's Privacy Preserving Measurement (PPM) working group, which we will implement in Divvi Up.

PPM's design is informed by our experience with Prio in ENPA, but its ambitions go beyond that. Prio does really well when the values being measured are numbers with well-defined boundaries. For example, you might be measuring how many users click on a button in an application or the average request latency when clients interact with some server. But it doesn't work as well when the measurements are arbitrary length strings, like a URL. Fortunately, the inventors of Prio have published a new system called Poplar, which addresses what's called the private heavy-hitters problem:

In this problem, there are many clients and a small set of data-collection servers. Each client holds a private bitstring. The servers want to recover the set of all popular strings, without learning anything else about any client's string. A web-browser vendor, for instance, can use Poplar to figure out which homepages are popular, without learning any user's homepage.

Remarkably, Poplar has the same overall "shape" as Prio: many clients secret share their inputs and transmit them to non-colluding aggregators who then compute aggregate shares that reveal nothing about any input. We're betting that there are more systems with this shape out there, which is why we designed PPM to coordinate the execution of any such system that can be expressed as a Verifiable Distributed Aggregation Function, another IETF standard that we are helping to design.

In this post, we're going to discuss some of the challenges we encountered while building and running the ENPA system over the last two years, along with the learnings we then applied to the design of Divvi Up and the underlying PPM standard.

Fig. 1: System diagram of the Exposure Notifications Private Analytics system.

Trusted key distribution

Provisioning secrets and security parameters is always challenging in distributed systems, and it's even harder in MPC, because there may not be any single identity or secrets distribution system that spans all the participating organizations. In ENPA, this led to two separate but related challenges: establishing trust between the participating servers (run by ISRG, NCI, MITRE, Apple and Google), and the trickier problem of trusted distribution of the aggregators' encryption keys to the millions of Apple and Google mobile devices running EN. In particular, we wanted to enable revocation of encryption keys, and didn't want the clients to ever need to communicate directly with the aggregators.

The server-to-server case was solved by bootstrapping trust from the Web PKI. Servers fetch each other's security parameters (such as mailbox addresses or public keys) over HTTPS. Given that we have well-defined mechanisms for issuance, revocation and transparency of certificates, it was tempting to use the Web PKI to distribute aggregator encryption keys to clients, but we learned that this is inadvisable.

Issuing a certificate whose "Extended Key Usage" field is "serverAuth" but will not be used for something that isn't TLS, such as the encryption scheme used in ENPA, is questionable at best under the CA/Browser Forum's Baseline Requirements. Such issuances are not explicitly forbidden, but this sort of technically-okay-but-not-intended usage of TLS certificates poses a risk of eventual distrust to any certificate authority that does this. It also makes it harder for the Web PKI community to improve and clarify standards to make TLS safer for the Web in the future.

Our solution in ENPA was to issue certificates over encryption keys from an Apple-controlled CA that is trusted by mobile devices for this specific application but not generally trusted by Web browsers and hence not subject to the CA/Browser Forum requirements.

In PPM (and hence Divvi Up), clients fetch either aggregator's security parameters directly over HTTPS, eliminating the need for bespoke certificate constructions or other means of establishing trust in a server without ever connecting to it.

Multi-cloud deployments

The privacy guarantees of MPC systems like ENPA rely on a non-collusion assumption, which means that no single organization controls both of the aggregator servers in the system. To rule out the possibility of anyone being able to reassemble input shares, we decided to deploy the two aggregators to two different public clouds, namely Amazon Web Services and Google Cloud Platform. That meant the aggregator had to be portable across clouds, which takes significant extra effort and limits usage of any features exclusive to either cloud provider.

We were also concerned early on that the batches of inputs being uploaded to aggregators would be on the order of hundreds of megabytes, perhaps too large for HTTP request bodies. To simplify the implementation of aggregation servers, we decided to use AWS S3 and Google Cloud Storage buckets as mailboxes in an asynchronous messaging scheme.

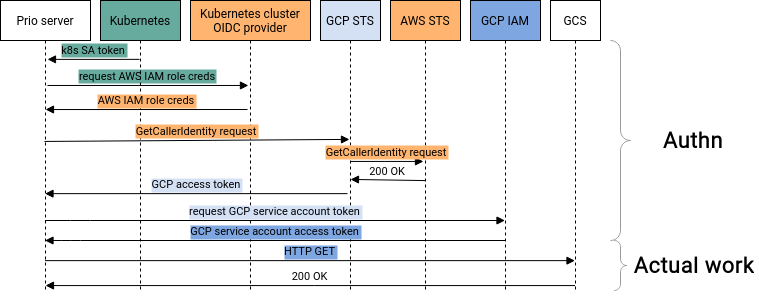

That means we had to figure out how to get workloads in one cloud to securely access resources hosted in the other. Fortunately, the security teams at AWS and GCP have worked to make this possible without sharing any secrets between two deployments, which is quite an impressive feat. That being said, the resulting authentication flows are very complicated.

Fig. 2: Multiple credential exchanges are required for a workload in Amazon Web Services' Elastic Kubernetes Service to authenticate to Google Cloud Platform services.

For example, for a workload running in AWS' Elastic Kubernetes Service to make authenticated requests to Google Cloud Storage, it has to perform four different credential exchanges, going from a Kubernetes service account to an AWS IAM role to a GCP access token to finally get a credential for a GCP service account authorized to do something like download an object from a storage bucket.

All of these token exchanges are there for a good reason, as each represents a transition across a meaningful security boundary. The overhead from obtaining the tokens is negligible because the credentials can be cached for a configurable period on the order of an hour. The concern is that to get this working, you have to orchestrate the deployment of AWS IAM roles, GCP service accounts, OIDC identity providers and Kubernetes role based access control across multiple cloud accounts to securely federate each with the other. Each of those resources is an opportunity to get something wrong and leave a security hole in your deployment that could undermine the privacy guarantees offered by the new cryptography we are using.

We expect that Divvi Up subscribers are going to care about cloud or compute platform diversity, but the PPM standard defines all the protocol interactions in terms of HTTP requests and responses, which makes it easier for implementations to interoperate regardless of what platform any server happens to be running on.

Testing and debugging

End-to-end integration testing of distributed systems is always a challenge. This becomes significantly harder in MPC because of the complexity of coordinating deployments and tests across all the participating organizations, who don't have a common release process, deployment system, or even calendar server.

This is especially true in a privacy-preserving system like ENPA, in which incorrect or corrupted intermediate outputs are deliberately indistinguishable from valid ones. In ENPA, an end-to-end test requires setting up two devices to simulate an exposure, an ingestion server and two aggregators. Those software components span three different organizations, at a minimum, meaning that tests become a complicated logistical exercise. To ensure test results are predictable, we also had to set up custom client builds configured to disable features like differential privacy that deliberately randomize inputs.

This problem is easier to solve in the context of Divvi Up because of the PPM standard. Many integration problems can be caught much sooner if every implementation targets a common specification and can test against reference implementations or test vectors. However, a robust protocol specification doesn't completely eliminate the need for integration testing. We can learn a lot here from our colleagues at Let's Encrypt, whose staging environment serves both as a testing ground for Let's Encrypt engineers but also as an integration test environment for teams integrating their ACME clients with Let's Encrypt.

Conclusion

ISRG is applying everything we've learned from building ENPA, a privacy preserving system for aggregating epidemiological metrics, to some exciting new projects. We're working with a team of leading researchers and practitioners on standardizing Privacy Preserving Measurement through the Internet Engineering Task Force, which generalizes from Prio's architecture to describe the execution of several privacy preserving aggregation techniques, like Poplar and hopefully others in the future. We are also building Divvi Up, our nonprofit service to bring PPM-based metrics to everyone.

If you want to get involved, consider participating in the standards process through the IETF, or contact us if you're interested in subscribing to Divvi Up. If you want to learn more about ENPA, check out the talk we gave at RWC 2022 or the whitepaper describing the system's cryptography.